1970s – The original Breeders

Kim Deal: “Me and Kelley had songs. A hundred songs. Kelley got a bass guitar, and, being in high school, we wanted to join a band. But you could not play in a band if you were a chick in Huber Heights, Ohio. If you sang a Pat Benatar song and played tambourine, that was acceptable. So we ended up playing the truck stops. The Ground Round. I remember men ordering me and Kelley sloe-gin fizzes when we were 16. We opened for the Allman Brothers once at McGuffy’s House of Draft. When we got there I was pretty nervous because there were motorcycles in the parking lot. But when bikers see young girls with an acoustic guitar harmonizing on a Hank Williams song, you know they’re going to like it.”

(Allman Brothers show was possibly Friday, August 17, 1979)

By 1978, they had a home studio with a mixing board and an eight-track recorder. Kim even spliced the electrical cords. They played open mic shows, biker bars, the Ground Round, truck stops: Kim on acoustic guitar; she and Kelley harmonizing on Hank Williams (“I Can’t Help It”), Neil Young, and Little Feat songs. Among their originals was one called “Do You Love Me Now?”

Kim Deal: “These tough big macho biker guys…you could make them cry. You really could, It’s a lot different to college-age-type kids who just think ‘there’s no fuckin’ way we’re going to sit around listening to this shit.’“

Even back then they played under the name “The Breeders”.

Kim had heard it was slang for heterosexuals in the homosexual community. “It’s like ‘yeucch! they’re breeders!,’ like a ripe, stinky thing, it could also be men’s attitude towards women, and women about themselves.”

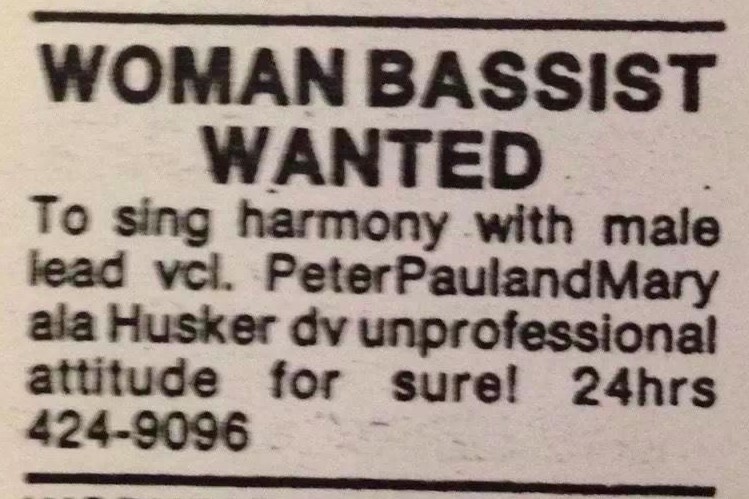

Kelley became a systems analyst for a defense contractor. Kim met John Murphy, a Massachusetts native working at Wright-Patterson. They married, she moved back to Boston with him, got a job in a doctor’s office, answered a “bassist wanted” ad in the Boston Phoenix

1980s – Moving to Boston

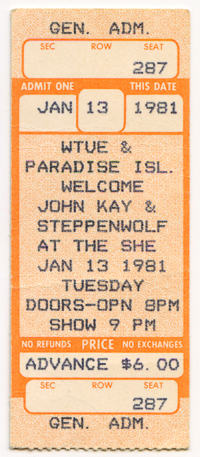

In the early 80s, Kim and Kelley were still performing local shows.“At that time they were called John Kay’s Steppenwolf, and there was only the singer, what I remember most is that there were about thirty Harley-Davidsons outside the door of the club.” – Kelley

“We were a duo, Kim & Kelley, and we did covers of Delaney & Bonnie, Blind Faith, Hank Williams, Elvis Presley… Also an Elvis Costello one, (The Angels Wanna Wear My) Red Shoes.” – Kim talking about opening for John Kay’s Steppenwolf.

In January 1985, Kim moved to Boston with her (now ex) husband John Murphy.

Kim Deal: “My ex-husband, John Murphy, was from Boston. He worked as a computer programmer, and he was transferred to the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Fairborn, Ohio. My brother was at the same company and he introduced us. John wanted to go back to Boston. Boston, that’s the coast, and they’re not weird about playing with chicks. I got a job working at a doctor’s office in Brookline. I was hired to do lab work. I loved the microscope and cellular biology. If you gave a stool sample, I’d be the one swabbing it on a plate of agar and seeing what grows.

John Murphy: “Kim had made a tape with her sister. She used the equipment she had, which wasn’t much, electric drums, stuff like that. She had an eight-track, so she hired somebody to help her produce it, and then she sent it around, and that was actually the first publicly distributed Breeders tape. She recorded it in Dayton and produced it in Massachusetts, and she sent it out to all the radio stations just like a regular person would do, and nobody picked up on it at all. She didn’t give it much time, but she figured, well, I’m not going to make it on my own, I don’t know anybody, so she started looking at ads. And that’s when she saw the famous Phoenix ad. I remember her pointing it out to me afterwards.“

1988 – Kim Deal and Tanya Donelly form the 2nd incarnation of The Breeders

Kim Deal: “Yeah, we wanted to play. So she would show me her thing,

and I would say, “Oh look, I know this thing.” But then we started

having songs. Like “Oh, that’s good, you can do this there.” “Oh

yeah, that’s cool.” She thought it would be a good idea, she wanted

this song to be a disco song. And so we thought, oh we should do a

disco song, that would be so fun, so we tried to enlist some peo-

ple to help us and some people did. David Narcizo helped, and

there was another drummer in town that helped, too. That was fun.

We even went to a rehearsal space – me and her and Narcizo, to try

to come up with this disco song. But we didn’t. But anyway that

started getting us to think, oh yeah, we could do these songs, and

these songs. There was a lot of time.”

“It was a Boston nightclub where Deal and Donelly first hatched the plan, in a drunken conversation, ‘to write a disco song and make a lot of money,’ says Deal. This had gone as far as recording Donelly’s track ‘Rise’ in a disco fashion with Narcizo on drums, but Deal and Donelly’s schedules weren’t to coincide for another eighteen months.”

Tanya Donelly: “It was a way to extend the tour a little bit because we

were enjoying hanging out. And so first we were just playing for fun,

and then Kim decided that she wanted to do it more seriously. We

used to go out dancing every night after the tour and we used to go

dancing in Boston. We loved dancing to, like, Black Box, Neneh

Cherry, and a lot of English dance stuff—we just would dance to any-

thing. So we just decided we were going to-do it, too. I think if we

had put a little more backbone into it we could have done it, but it

just wasn’t happening for whatever reasons. I think probably we

weren’t quite ready for a concept project at that stage in our lives.

So that kind of just morphed into doing the Breeders. And that would

actually be mark two of the Breeders, because Kim and Kelley had

been called the Breeders when they were teenagers. I didn’t even

meet Kelley until probably a year after I started hanging out with

Kim. So she was not interested at that point, it was only after I left

that she came into the fold.”

1989

John Murphy: And then Kim started talking to another friend of theirs, Carrie Bradley, who was a violinist and singer in another band [Ed’s

Redeeming Qualities]. So those three formed the crux of the original Breeders, and they had four drummers coming in and helping them

do the demos. The bass player on the original demos was another friend of ours, Ray Holiday, but Kim is a perfectionist, so she redid some of his parts. Then they produced this demo and they played one show only with that lineup at the Rat, and it was billed in the

Phoenix as a Boston girl supergroup, and they brought the tape to 4AD because everybody told them it was good, which I did, too. So

then when they submitted it into Ivo they were like, this is great, we’d like to do this, but we’ll get a real producer and do the songs over again, because they treated it purely like a demo. To this day I think the demo tape was more accessible than Pod, the first Breed-

ers CD.

Tanya Donelly: [Writing Pod] was really fun, just hanging out at Kim’s

house while John Murphy was at work. After they split he still had Mente, he was still doing stuff around here, and I think it was relatively amicable. [Kim and John’s breakup] wasn’t long after we got home from the big Pixies/Muses tour. I think there was just kind of a shift in what they wanted in life.

Joe Harvard: “Once the Pixies were flying, Kim obviously felt the need

to do something else and something that was even more enlightened. Because it had more of a female element, let’s face it, it was more enlightened. And I think they felt the need to push that further than they could in the Pixies, where she was one out of four, so they

did the Breeders. So Kim had done her demos, she did six tunes,

“Lime House,” “Doe,” and “Only in 3’s,” and Paul Kolderie who

was the best engineer we had at that time, had engineered the

Breeders stuff, and in Kim’s world, it was too clean, it was too per-

fect. “I want it messed up.” Not surprisingly, she would ask me. She

said, “I don’t want to send it to 4AD this way,” so I went in and

remixed five of those, and that turned out really well, we had fun. We

sent it to Ivo, he actually called me, I had never talked to Ivo, he

said, “Joe, this is absolutely magical, beautiful stuff.” What happened was Tanya’s songs for that second Breeders record became

the first Belly record because she left the Breeders right after that.

During late 1988, Donelly and Deal hung out at the latter’s house in Boston and worked on songs. Carrie Bradley, a violinist and singer in the Boston alt-folk band Ed’s Redeeming Qualities, got involved. As did the latter band’s manager and Deal/Murphy friend, Ray Halliday, who played bass and co-wrote a few pieces (“Doe,” “Glorious.”) “Kim is a perfectionist, so she redid some of his parts,” her now-ex-husband Murphy said.

Using various drummers, Deal and Donelly demoed most of what became Pod, including “Only in 3’s“, “Doe” and “Lime House,” along with “Silver” (soon recorded by the Pixies on Doolittle), “You Always Hang Around” (later turned into “Divine Hammer”) and a song that would appear on Last Splash: a cover of Ed’s Redeeming Qualities‘ “Drivin’ on 9.” 4AD’s Ivo Watts-Russell, entranced by the demos, gave Deal and Donelly $11,000 to make a record.

1989 The opportunity arose when Charles Thompson announced he was going on a solo tour. ‘I thought that we were a band, and I didn’t get the solo thing, so I thought I’d do something solo too. – Kim

Tanya Donelly: For contractual reasons, because of her contract with

Elektra, my contract with Reprise, we couldn’t both be the primary

songwriter on the record, so the concept was, and it was an extremely idealistic one, was that she would write the first record and it would

come out on her label, I would write the second, it would come out

on mine. Under hopefully “the Breeders,” but if either of them

balked at that we would change the name of the band. To something. I don’t think that was ever really figured out. The whole first

Belly record is demoed at Fort Apache, under the Breeders, and Kim

plays on it, because that’s what it was gonna be. So the demos for

the first Belly record Joe did with us, and it was me and Kim and it

said Breeders on it, because that’s what it was supposed to be for.

So he produced those and they came out really great. I think I have

the tape somewhere, I think Ivo’s the only person that has a copy of

it, though.

Ivo Watts-Russell: I had a good working relationship with Kim.

“Well, okay, so you want to record, let’s go to the studio in Scotland,

we will get Steve Albini out there, it will be fun for you to be out

there,” done in time off that Tanya had in Throwing Muses before

she left. I don’t know if she had the best of times with Albini on that

record.

Tanya Donelly: I loved Big Black, which I think really surprised Albini

because he had sort of a warped impression of me when we first

met, He told me that if he drank my bathwater he’d probably piss

rosewater. He thought I was just kind of girly. We ended up getting

along really well and he’s a very sweet person. I’m probably going to

requote Joey right now, it’s probably the last thing he’d want anybody to say about him, but I was just so impressed by him in the studio, too, just how decisive he is and he just knows how to get a sound that he has in his head. He also made decisions about cutting down some of the harmonies which we balked at initially, but he was 100 percent right. Some of the parts, it’s just better having her single voice, it makes it more effective and sadder and sort of just more focused.

Steve Albini: Kim had some songs and some demos put together with

a version of the Breeders that used a slightly different lineup and

she asked me if I knew of any drummers that would be appropriate

The band name The Breeders could have been some sly feminist statement along the lines of The Baby Machines, but it was actually an in-joke between Kim and sister Kelley, being homosexual slang for heterosexuals: ‘That they saw a straight couple’s goods as disgusting was so funny to me!’ says Kim. ‘Later, the meaning became more layered, like one man saying to another, “He’s a breeder, too bad”.’

The Breeders needed a rhythm section as Deal wanted to play some guitar – it was easier to combine with singing on stage, she says. For the bass, she called on Josephine Wiggs of The Perfect Disaster, a British equivalent to the Paisley Underground sound that had supported Pixies in London. ‘She was musically intelligent, self-deprecating, and easy on the eye,’ says Deal. In return, Wiggs found Deal complex and entertaining company.

‘I was in Frankfurt when Pixies were playing in 1989, and we got to hang out, we sat in the railway station next to the venue, where Kim insisted there was enough clearance between the train and platform to dangle her knees over, which didn’t seem a good idea! She was hilarious on that level, a risk-taker, who liked to live in the moment. At 3am, everyone else had left and she had no Deutschmarks for a taxi, and no other way to get back to the hotel, which was out at the airport! My friend had to pay for her.’ – Josephine

Deal had wanted twin sister Kelley to play drums, but she couldn’t get leave from her current job (as a program analyst), so Steve Albini – Deal’s choice of producer for his no-nonsense approach to analogue sound – had brought along Britt Walford, a member of the Louisville, Kentucky band Slint, whose Albini-engineered debut album Tweez had mastered a slow, stark sound at total odds with the fast, FX ear-bashing of alternative rock. As the only male Breeder, Walford insisted that he adopt a pseudonym, settling on Shannon Doughton when Deal rejected his original suggestion of Mike Hunt. Walford was a very different, minimalist drummer to the likes of Dave Lovering, and with Albini stressing live performances and quick takes, the album only took two weeks to record at Palladium. It didn’t sound like a country music record for one moment.

The album turned out to be Deal’s deal. She sang and wrote all the songs, with the idea that Donelly would take over when a second Breeders album got made. The sole Deal/Donelly co-write ‘Only In 3’s’ didn’t break with the record’s stripped, wired dynamic; seven of the twelve songs were closer to two minutes than three. Ivo’s suggestion to cover ‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’ resulted in one of the most inventive Beatles covers in years.

Deal denies she felt liberated by the experience. ‘I didn’t think, Charles won’t let me shine, now this spirit’s come over me, I’ve been given a chance to sing my songs, like TV Moment of the Week. All I cared about was it sounding good. And I didn’t know how the songs would go. One moment, I thought it sounded awesome, the next minute not.’

A surprise studio guest was Mick Allen, who had spent a reputedly riotous night at Manchester’s Hacienda club with the Boston brigade and later added murmured backing vocals to ‘Oh!’ Deal liked Allen, from his bass lines to his bolshie character. ‘Mick had a big fucking mouth, he’d talk trash constantly and destroy everyone in front of him, but not in a mean way, more very funny, all snotty with disdain.’ – Kim

Pod – the album’s title inspired by a painting Deal had seen in Boston – ‘and it’s a good word’ – was given one of Vaughan Oliver’s most memorably surreal images with the aforementioned belt of dead eels attached to his underpants. Albini considered the album one of his best sessions, and John Peel was smitten enough to allow The Breeders special dispensation to record a session at Palladium rather than the BBC’s west London studio.

Pixies didn’t sell that many singles but they did albums, and Pod reached 22 in the national UK chart. Santiago says that the other Pixies supported Deal all the way: ‘Especially Charles.’

Deal subsequently recorded a new Pixies album, though Ivo wisely kept the two records apart to avoid any conflict of press duties and reduce the number of unavoidable comparisons. Ivo also kept the two albums separate in terms of licensing, thinking that Pod was more suited to an independent label. He managed to persuade Elektra of this thought, and licensed Pod to Rough Trade America.

Pod was released at the end of May, to be followed six weeks later by Pixies’ single and the band’s third album a month after that. Two releases acted as convenient buttresses in between, one from another of 4AD’s circle of distressed male-female relationships.

1990

Rough Trade US; ‘The Breeders never got any money for Pod,’ recalls Kim Deal. ‘We were told that the money Rough Trade America made was reinvested in Butthole Surfers’ piouhgd, and then the label went bankrupt. When Robin [Hurley] joined 4AD, I asked if he was going to bankrupt this place too!’

Vaughan Oliver: “It was a reaction to an all-girl band, called The Breeders, their album title Pod and the vibrant colours I was getting from the music,’ he explains. ‘To me, it needed a strong male response. The eels are phallic, but I’d seen an image of a belt of frankfurters that stuck in my mind, so I developed that. When it came to shoot it, I couldn’t get anyone else to do the job, so I did it. There was blood everywhere … but I knew one of the shots would work!”

“A male fertility dance in response to some very visceral music from an almost all girl band. Kim Deal has a sense of humour to which I was trying to appeal.” – Vaughan Oliver

Safari era:

As Pixies simmered with even more unresolved tension, Kim Deal decided to reconvene The Breeders. While on a UK tour with Pixies in late 1991 (June or more likely July), Josephine Wiggs had received a call from Deal, saying she had a song she wanted to demo called ‘Do You Love Me Now?’, written by the Deal twins during their truckstop-gigging days. The pair recorded it at Wiggs’ home in Brighton and hired Spacemen 3’s Jon Mattock to add drums. Months later (november), the original Breeders plus one met in New York to record three more new songs. Despite being a relative novice on guitar, Kim’s twin sister Kelley was set to replace Donelly, who was busy with her own solo plans, yet the latter turned up anyway, making it the one record with five Breeders. Playing what Wiggs calls ‘stream-of-consciousness guitar playing’, Donelly’s contributions lifted the tracks. But the sensual, prowling nature of ‘Do You Love Me Now?’ indicated The Breeders would survive without her. The closing cover of The Who’s ‘So Sad About Us’ on the resulting five-track EP Safari could conceivably have referred to Pixies, but the truth was, Kim Deal was simply smitten with Who bassist John Entwistle.

Last Splash

In the summer, The Breeders had played some shows, first at Kurt Cobain’s request, supporting Nirvana at two Irish shows (Dublin and Belfast) in June 1992. On a short European tour in early autumn, they’d started playing a new song with an irresistible stop-start momentum and layered hooks. Kim Deal had named it ‘Grunggae’. ‘The name was a joke, combining “grunge” and “reggae”,’ Josephine Wiggs explains, ‘because Kim thought the accented riff resembled the accenting in reggae.’

During Charles Thompson’s interview for BBC Radio 5’s show “Hit the North” on the 13th of January, 1993, Charles announced the end of the Pixies:

“No. I haven’t fallen out with anybody, except maybe Black Francis. I sort of have fallen out with him, so therefore out of the Pixies rises something else. I’m just giving it my best shot.”

Is the Pixies finished?

“Yeah. In a word, yeah.”

‘The last show we ever did was in Vancouver, at the end of a tour, and we all just went home, everybody was under the impression that we were taking a year off, like a sabbatical, but it never came to that. Charles started his own album, and Kim had The Breeders. Three or four months later, Charles called, out of the blue, at my girlfriend’s house, to say he was splitting the band, and that he’d faxed Kim and Dave.’ – Joey Santiago

Ivo says the myth that Thompson informed the other Pixies by fax still annoys him. ‘It’s true Charles wrote a fax, but also that Ken [Goes] refused to send it, saying he wasn’t paid enough to do something like that.’

In 2012, Santiago says the only fax was the one Thompson sent to Ken Goes. Kim Deal recalls getting a call while in the studio recording a new Breeders album. ‘I had no reaction other than I wasn’t surprised,’ she says. ‘It had clearly run its course.’

‘You’d really have to ask Charles why but I’m sure the tension between Kim and Charles had something to do with it. Charles hasn’t even discussed it: it’s not his style to analyse. It wasn’t like we ended up fist-fighting or arguing constantly, it was more unspoken tension. Kim phoned me and said, “Did you know that the Pixies just broke up?” and I replied, “I’d be more surprised if we got back together”. I was shocked but what could I do? I thought it was premature because I really thought we could do more. Ending that abruptly was weird.’ – Joey Santiago

Ivo’s first port of call when he left the UK for the States that year was San Francisco. There, he visited The Breeders during the new album’s closing session with Mark Freegard, who had engineered the Safari EP and progressed to co-producer. Kelley Deal was now a permanent fixture in the band, having quit her job as a technical analyst when denied more leave; and with Britt Walford choosing to stay focused on Slint, Deal had snapped up Jim Macpherson, the drummer of the Dayton band The Raging Mantras. He had regularly posted flyers through Deal’s letterbox until she turned up to see one of their shows. Macpherson was a different proposition to Walford: ‘Jim was extremely powerful, but also sensitive, which was a very interesting combination,’ says Josephine Wiggs.

Driven harder by Macpherson, The Breeders started to resemble a different band to the one that had made Pod, especially armed with the new version of ‘Grungae’, which was now called ‘Cannonball’. It also had a new deeper, rippling bass intro. For inspiration, Deal singles out the basslines of Mick Allen, especially the Queer cut ‘Louis 14th’: ‘warm and oozing, up and down the fretboard,’ says Deal. The actual finished part was down to a mistake: Wiggs had played the last note flat but everybody decided it was better for it.

Freegard recalls the first time he heard Kim’s newest batch of songs: ‘She was playing them down the phone, her guitar perched on her knee, saying, “Kelley, play the lead guitar I taught you” as I made notes.’ But this impromptu approach was drastically altered in the studio, as a three-week booking turned into four long months with Kim painstakingly building a new sound, full of overdubs and treatments.

‘All of a sudden, independent music had become a tag word, a philosophy,’ Deal explains. ‘There had been this college music network across the country, in the early days of R.E.M., and then Pixies, Throwing Muses, Sonic Youth. We’re all going overseas, and someone sees this young community that marketing people can reach, so there’s sponsorship and advertising dollars, and you’ve got this thing called Alternative Music, a tag word that I was told market research had shown piqued the interest of readers from the age of fifteen to thirty-two.

‘Nirvana just blew it all up. Grunge was in Vogue magazine, and bands were signing to majors who were creating indie labels for them. The whole phenomenon was cynical and strange to me, so to have our album sound so produced was a reactionary move. But on “Cannonball”, I’m screaming the last line, and we’re manipulating my voice all the way. It sounded great, but it wasn’t a template for radio.’

‘It was an exhausting recording because things were so unpredictable,’ says Freegard. ‘For “Flipside”, for example, Kim wanted it to sound like a bad cassette. The project became one big edit, but no computer in sight. Kim wouldn’t have it. It was exhausting and stressful for everyone, but mostly Kim, because of expectations, from management, label and herself. It took its toll.’

The shed-load of pot that Kim was consuming might have made the sessions a lot of fun, but would have only added to the trial. Freegard discovered pieces of burnt silver foil in the lounge area, suggesting harder drugs were also being consumed, but any such use was kept hidden from the other members. The sessions continued in San Francisco, where the band stayed on houseboats as the last pieces of the musical puzzle were slotted into place.

Co-producer Mark Freegard recalls how exhausted the band had been after finishing the album, yet its sound and mood was exhilarating and mostly upbeat, warm and oozing like the ‘Cannonball’ bass intro. A lyrical snippet from the track donated the album’s title: Last Splash. With an equally addictive chorus hook and Kim’s vocal approximating a loudhailer, ‘Cannonball’ struck the same balance between left-field adventure and pop accessibility as ‘Monkey’s Gone To Heaven’. When it was released as a single three weeks before the album, MTV’s Buzz Bin programmers were instantly on the phone. Kim Deal could make cookies after all.

‘Cannonball’ was backed by a cover of Aerosmith’s ‘Lord Of The Thighs’, sung by Wiggs with deadpan detachment, tapping Kim Deal’s fondness for dumb American rock. But Kim had cracked the mainstream herself. ‘At the end of mixing Last Splash,’ recalls Freegard, ‘Ivo came in to listen, and he said, “Mark, this is going to be the most successful 4AD record ever”. I was staggered that he’d say that, but he was right.’

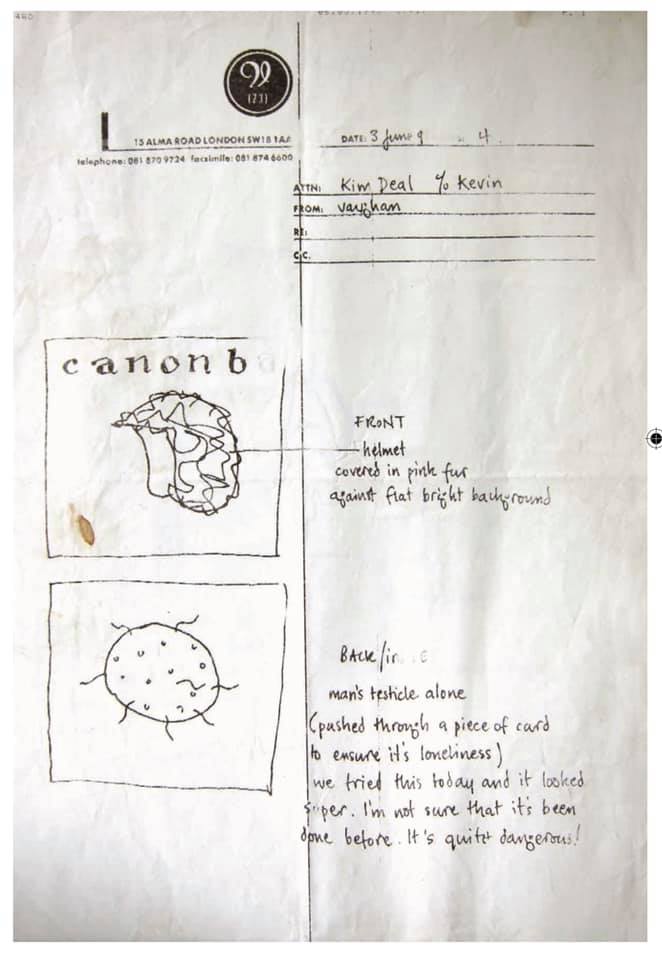

It would have been interesting to see the reception if Vaughan Oliver had got his way over ‘Cannonball’; for the back cover he’d suggested the image of a singular testicle ‘pushed through a piece of card to ensure its loneliness’, as Oliver wrote on a fax to the band, alongside a drawing of said testicle. ‘We tried it today and it looked super.’ Well, it was one interpretation of a cannonball. ‘For the back of Safari,’ Kim recalls, ‘Vaughan had wanted the texture to be an areola. I said, “Can we not have naughty bits?”’

Oliver’s front cover design, of a fur-covered American football helmet, effectively captured the wolf in sheep’s clothing that was The Breeders. With a video co-directed by Kim Deal’s pal (and Sonic Youth bassist) Kim Gordon and the fast-rising Spike Jonze, ‘Cannonball’ topped Billboard’s Modern Rock chart and entered the Billboard’s national top 50 – Pixies had never achieved that, for all the

acclaim and influence. In the UK, the single only reached 44, but Last Splash reached the top five. The album was the only time 4AD commissioned a billboard advert, the album cover’s vibrant red heart splashed with blood visible on the flyover into Hammersmith, photographed by the appropriatedly named Bournemouth University student Jason Love. Last Splash wasn’t only about ‘Cannonball’ or the second, relatively gentler single ‘Divine Hammer’, or the third, heavyweight ‘Saints’. There was a breath of style, from grungy sludge (‘Roi’) to breezy country rock (‘Drivin’ On 9’, originally by US alt-folk band Ed’s Redeeming Qualities, whose violinist Carrie Bradley had become a regular Breeders contributor) to Pixies-style turbulence (‘No Aloha’). The album shot past 500,000 sales towards the million mark. Again, Pixies had never had such success.

The night of The Breeders’ 13 Year Itch show, while loading Insides’ equipment, Tardo saw lines of Japanese kids outside. ‘Only then did I appreciate how much people were obsessed with 4AD,’ he says. Yates was equally amazed to see Kim Deal bouncing into their dressing room: ‘She said, “Let’s talk to these nice Insides people”.’

1994

Life certainly hadn’t turned out easy for Kim Deal in the wake of Last Splash. A strained touring schedule culminated in the 1994 Lollapalooza tour, fourth on the bill behind The Smashing Pumpkins, Beastie Boys and George Clinton & The P-Funk All Stars. Deal felt that they needed a record to coincide with the festival, and responded to an album that had now sold 1.5 million copies with a vinyl-only ten-inch EP of bristling lo-fi, in case anyone had thought the band had forgotten its roots. Joining the atonal, thrashy title track of the Head To Toe EP, written by bassist Josephine Wiggs, and the appeasing presence of Last Splash single ‘Saints’ were covers of songs by lo-fi underdogs Guided By Voices (‘Shocker in Gloomtown’) and Sebadoh (‘Freed Pig’).

Josephine Wiggs says that Head To Toe was a response to the difficulty of reproducing the layered sound of Last Splash on stage. But she also acknowledges that there was more to it: ‘Kim would have felt under a lot of pressure to carry on, and that the next album must be even bigger and better.’

Deal had also notably turned down a Levi’s ad campaign that wanted to use ‘Cannonball’. ‘Everyone knew that if Kim had agreed, The Breeders would have been huge,’ says Ivo. ‘“Cannonball” was the tune of 1993, but she wouldn’t be defined by it.’

The Deal twins had made Last Splash on a varied diet of drugs, and after The Breeders had come off the Lollapalooza festival tour in September 1994, Kelley had been arrested for possession of heroin. She admits that she had been using for years – ‘I was a drug addict and an alcoholic waiting to happen’ – even when working in office jobs that required security checks.

The outcome of the court trial in January of 1995 was a spell in rehab, which she did in St Paul, Minnesota. Whatever was to follow for sister Kim, she knew it couldn’t be The Breeders: ‘I really didn’t think they’d ever come back.’ Josephine Wiggs says Deal announced that she wanted to pursue a solo project, ‘something quick and dirty, under the radar,’ says Wiggs. ‘Something without the pressure of following up “Cannonball”. It’s always a good idea to do something in a different way. And why would you want to stop someone if that’s what they want to do?’

Wiggs recalls that Kelley Deal had been concerned with this news. ‘Kelley made moves to try and orchestrate us all playing on it, but I told Kim that if it was to be a Breeders record, I’d come out to

Dayton, but it was clearly going to be a side project.’

But after Kim Deal had begun to record in her basement, she changed her mind and decided her new songs should be road-tested with a band. Tammy Ampersand and the Amps, later abbreviated to The Amps, was Kim, Breeders drummer Jim Macpherson and two other Dayton musicians, guitarist Nate Farley and bassist Luis Lerma. The songs duly road-tested, Deal then decided to use the band to record an album. It proved as difficult as the Last Splash sessions, a costly exercise, using five separate studios, one belonging to Robert Pollard of Guided By Voices (‘I Am Decided’ was a Deal–Pollard co-write). It wasn’t Nassau, but it was still expensive, except that this time Deal was searching for a raw, unproduced sound closer to the Steve Albini model.

‘Frankly, I was really struggling to deal with Kim’s lo-fi,’ says Ivo. ‘I couldn’t tell if it was truly a demo or if it was the sound she was trying to pursue. It was alike to Syd Barrett – she’s got this unique language to making music, but I didn’t understand the story and I couldn’t give any input, except to be encouraging when she’d call. I felt bad about not having come up with an alternate approach that might’ve been less costly and more fruitful. But, ultimately, I thought it cool that she was releasing something far removed from what everyone would have expected as a follow-up to an enormously successful record.’

‘Kim’s idea was of being able to re-create songs live for a club audience, without all that texture of Last Splash,’ says Kelley. ‘But really, she just wanted to break free.’

That’s precisely what Elektra didn’t want Kim to do. After the bankable success of Last Splash, Kim says the label had colluded with her manager to get her to sign an improved contract that would tie her to Elektra for much longer. ‘It meant the advances were bigger, like a couple of hundred thousand dollars for the next album,’ Deal recalls. ‘I told them, “I might make a tuba record next, I’m from the Midwest, I’m just a normal person”. I didn’t want to present myself as a fraud, to take the money and then not make the record they wanted. I said that they’d got the wrong person. I’ve tried, but I don’t have the killer spirit in me to generate chart sales for the sake of it.’

The Amps songs, such as the lead single ‘Tipp City’, a 128-second blast of bubblegum punk, showed exactly what she had meant. Nine out of twelve songs on the finished album, Pacer, came in under three minutes. Most were gristly scraps of lo-fi endeavour interspersed with weary melancholia, with none of Last Splash’s melodic summer. ‘Pacer was mostly a love song to Kelley,’ Kim admits. ‘I was feeling love, anger, worry, resentment, and grateful that nothing worse had happened.’

‘I know a handful of people who think Pacer is one of Kim’s best records,’ says Ivo. ‘I like it too, though it’s coloured for me by how much money she spent on a record that sounds like it cost very little.’

‘God damn, I was fucking nuts,’ Kim recalls. ‘I really did feel that I’d dropped the ball and the project lacked direction. I’d sent Ivo a demo of each song at a time, wrapped in a Polaroid, like a plug. It felt like an art project. I assumed he’d keep it like it was treasure, but he probably burned the cassettes in the backyard.’

Ivo says that Kim would sometimes stay in the flat above the 4AD office. ‘Martin Mills told me she’d sometimes stroll over to the pub across the road in her pyjamas. After Chris Bigg had asked her for the lyrics to Pacer, Kim left the flat with the message that the lyrics were upstairs, and she’d written them all over the bedsheet!’

One of those demos, ‘Empty Glasses’, even made it to the B-side of ‘Tipp City’. It’s not hard to imagine Elektra’s reaction to The Amps, though the label dutifully pressed up enough copies as if it was Last Splash part two instead of the anti-Last Splash. Unsurprisingly, Pacer sold poorly, leading to a surfeit of discounted copies in the shops that harmed further sales.

Deal wasn’t unhappy at the commercial return on a project that was dear to her heart, only at the business arrangements that she felt restricted her. She had first been upset when Rough Trade America’s licensing of Pod meant the album wasn’t included as one of the three albums that Deal owed under the terms of her Pixies contract with Elektra. ‘If I’d have stomped and screamed, Ivo would have let me go because he doesn’t like working with anyone if they’re not happy,’ Deal contends. ‘I had no reason to work with anyone else, but it didn’t seem fair, it seemed skeevy. I understood it’s a business, and a label puts in money and time, and then a band can break up. But no one was in the hole because of me.’

This time, she says, if she had refused to sign Elektra’s improved offer, they said they’d stall on the money that was in the pipeline. ‘Though Robin later told me they legally couldn’t do that,’ she adds. ‘I signed, as it would have been irresponsible to the other Breeders not to. Like Jim had just become a father again. And where was Ivo in all this? What was going on?’

Ivo has since apologised to Kim for his unavoidable absence – at this time, except for Mark Cox, he had kept news of his breakdown even from his friends

1996/1997

In 1996, Deal had decided The Amps’ live set needed bolstering with Breeders songs, and so that audiences didn’t get confused, she decided to resuscitate the band’s name. ‘It was … fine,’ demurs Josephine Wiggs. ‘I’ve thought a lot about this, and I’ve concluded that The Breeders is whatever Kim is doing.’

Kelley Deal, meanwhile, had followed the path of rehab by staying on in St Paul, Minnesota: ‘I didn’t know anyone in Dayton who wasn’t always shit-faced,’ she says. With a less demanding schedule, she’d formed a new band, The Kelley Deal 6000, and recorded two albums, 1996’s Go To The Sugar Altar and 1997’s Boom! Boom! Boom!, both similar in feel to Kim’s modus operandi. In 1997, Breeders bassist Josephine Wiggs says Kim had called to ask if she wanted in on a new Breeders album, but knowing that drugs might still be in the equation, Wiggs politely declined.

Kim had rehired Last Splash co-producer Mark Freegard to record a new album with the former Amps, plus Kelley when the timing was right. Kim not only had an advance for the new record, but a considerable amount of royalties from the sampling of Last Splash cut ‘S.O.S.’ by The Prodigy for the British electronic band’s global smash single ‘Firestarter’. ‘Even after seven weeks, and a studio cost of two thousand dollars a day, we had nothing to hear,’ says Freegard. ‘Kim got totally lost. She was taking substances and not wanting to go to bed, but she wouldn’t let the other musicians play. I had to give up on her.’

Drummer Jim Macpherson also bailed. ‘Kim had changed,’ he agrees. ‘The band had a totally different feel, and I was drinking and smoking with Nate and Luis. And I felt I wasn’t wanted. I also had two small children.’

On the subject of drugs, Kim simply says, ‘Pot, opiates and beer, I still love them all. I just don’t do them anymore.’ At the time, it turned her search for a sound that was only in her head into a purist obsession. ‘Digital production had burned through recording studios like crack,’ she recalls. ‘Everyone was densely layering everything, making keyboards sound like guitars, and I’m so reactive. I could

have put a hundred melodies on top but for me it’s more about drums and clean guitar. I worked really hard to keep it that hard and basic and people said it sounded unfinished! I was obviously doing the wrong thing.’ By 1998, she decided to jack it in and go AWOL in New York. ‘It was a lost year, and a lot of fun,’ she says, unrepentant. ‘I’d been touring consistently since 1987. So what was the worst that could happen? I finally met some guys in LA and moved out there, and I learnt to play drums, so it wasn’t wasted time.’

Title TK

However, the most anticipated return was Kim Deal – with Kelley again by her side. The sisters had been recording piecemeal since 1998, but the only track they’d managed was a cover of The James Gang’s ‘Collage’ (the B-side of the first single they’d bought together) for the 1999 soundtrack of The Mod Squad. Five other tracks from this period ended up on the new Breeders album, but it wasn’t until 2001 that Kim and Kelley toured again under that name, with three Breeders debutantes: guitarist Richard Presley and bassist Mando Lopez from the LA punk band Fear, and drummer Jose Medeles. The same year, Steve Albini was recalled to record the rest of the album, which Kim called Title TK. ‘That was the title I wanted to call Last Splash, but it didn’t make so much sense for that record,’ she says. ‘But here, it worked. Title TK sounds like I know nothing, even after fighting for so many rounds, not even a title for the fucking record! I thought it was funny.’

Although there were five Breeders on the credits, the album’s sombre, skeletal feel resembled the solo album that Kim had once intended to make. She was even playing some of the drums. 4AD bravely released ‘Off You’ as the lead single, a haunting ballad that laid bare the suffering and doubt that the sisters had endured. It couldn’t have been a greater contrast to ‘Cannonball’, and all the energies of Elektra to keep her on side failed. Deal had also to contend with the fact 4AD had changed. ‘I was very suspicious when I first met Ed Horrox, because he wasn’t Ivo. I also talked to Ivo, and to Vaughan, and it was all confusing. I didn’t know what anyone was doing. I don’t know if anyone suggested producers, but I’d wanted to shoo away everyone since everything had gone digital. But my 4AD contract ended with Title TK.’